Analyzing tweets from the controversial Pokemon-related #BringBackNationalDex hashtag with spaCy and Google Cloud

Discovering the top part-of-speech terms, sentiment, and mentioned Pokemon with the NLP library spaCy and Google Cloud

Breaking news: the Pokemon community is in an uproar. Last week, Game Freak, the developer behind the main Pokemon games, announced that the upcoming titles, Pokemon Sword and Shield, won’t feature the complete library of Pokemon. This library, known as the National Pokedex — hence the name of the movement #BringBackNationalPokedex — is currently made of 809 Pokemon. Besides being just a list of fantastic creatures, the complete Pokedex, represents the evolution and growth of the series that have conquered the heart of millions since its dawn. Personally, I find this a bit sad because I believe that this announcement goes against the essence and definition of what Pokemon is: gotta catch ’em all.

As a long-time fan of the series, and as a curious data person, I wanted to take a quick look at what the community was tweeting with the hashtag #BringBackNationalPokedex. Using Tweepy, a Python library for accessing the Twitter API, I quickly put together a script and let it run for a couple of hours collecting data. Then, using Python’s natural language processing (NLP) library spaCy, and Google’s Cloud Natural Language API, I analyzed the said data.

In this article, I’ll present my findings.

My goal of this experiment was to learn the top nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs the Twittersphere was sharing alongside the hashtag. Moreover, I also wanted to see which named entities, that is, a “real-world object that is assigned a name — for example, a person, a country, a product or a book title,” as defined by spaCy, were being used. Because no tweets analysis is complete without sentiment analysis, I ran the tweets through this sentiment model to get an idea of how happy or furious the people were with the decision. Lastly, out of curiosity, I was interested to know which were the most mentioned Pokemon.

The data and preparation step

The dataset used in this experiment consists of 2724 tweets, collected on June 13 and June 14, 2019, that include the hashtag #BringBackNationalDex. To clean it, I removed the mentions of retweets, e.g., “RT @account_name,” changed the instances of “Pokémon” to “Pokemon,” removed all the special characters (questions marks, commas, and such), and the https addresses from tweets that contained images. Something I didn’t do was to lowercase the tweets because by doing so, I could have lost some entities and proper nouns that otherwise wouldn’t have been detected by spaCy.

Top nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and entities

One of spaCy’s most powerful features is the part-of-speech (POS) tagging, which assigns a predicted label, such as noun and verb, to each document’s term. Using this, allowed me to discover the main idea or the context of the acquired tweets.

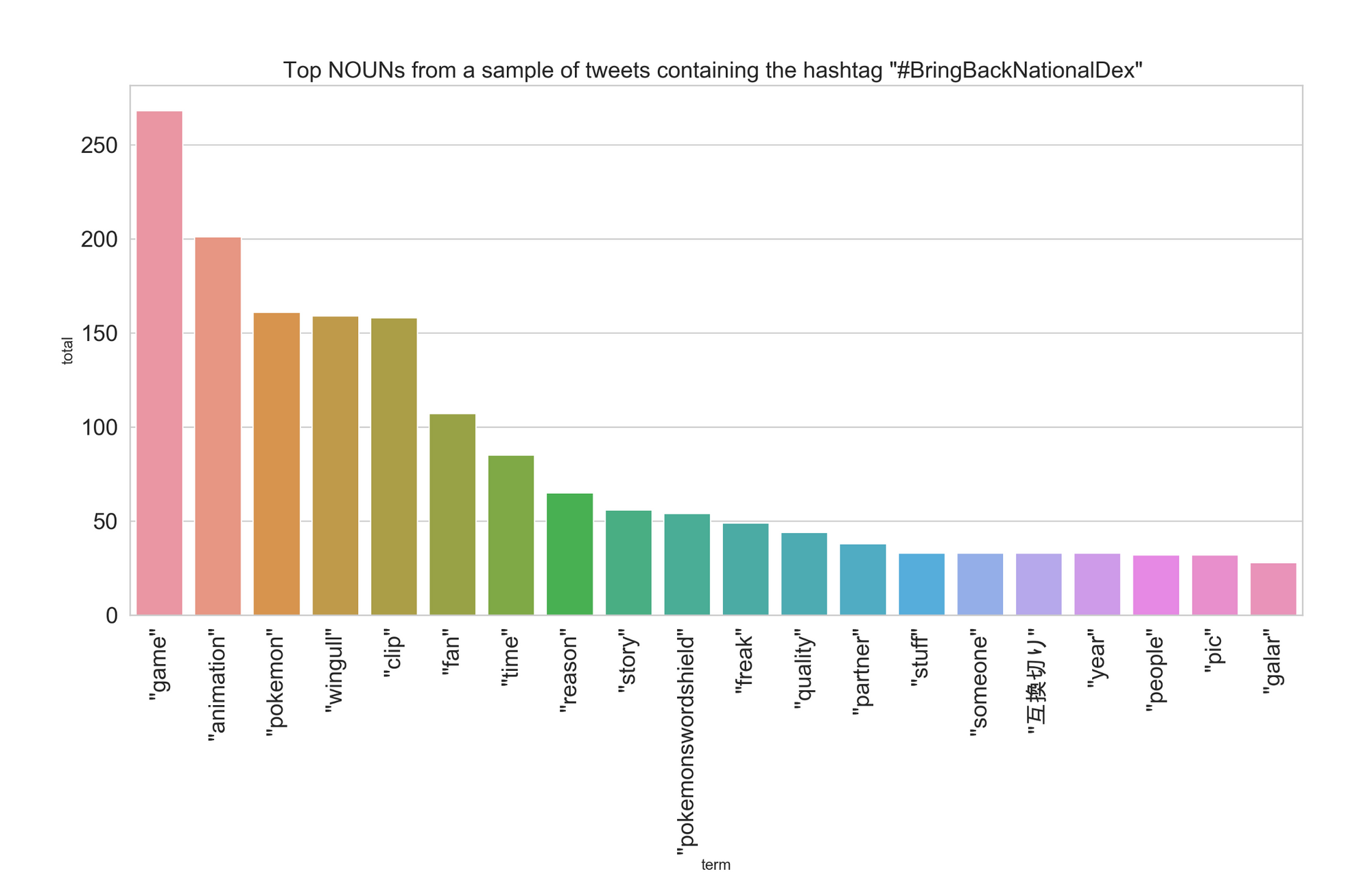

In elementary school, we learned that one of the most fundamental parts of a sentence is the nouns. These essential words exist for the sole use of naming things; that’s it, places, persons, ideas, feelings. Because of how essential nouns are, I wanted to open this article with them. Thus, for the first plot, I’ll present the top 30 nouns from the tweet corpus.

On the number one position, we have the term “game,” which is not surprising at all since the whole issue is regarding the upcoming Pokemon games. Following it is the term “animation,” which refers to the claims stating that the main reason why not all the Pokemon will be in, is that the developers don’t have the sufficient workforce to animate all the Pokemon. Then on spot number 3, is the word “Pokemon”.

The only Pokemon that appear on this list is Wingull, and that is because there was a tweet featuring a Wingull animation that went viral and was retweeted several times. Other important nouns from the list are “time”, most probably because of those who think the game needs more time before being released, the Japanese word “互換切り” or “Compatibility Switch”, which honestly I don’t understand the context (can someone corroborate this translation?), and lastly the proper noun “Galar”, which is the name of the new Pokemon region.

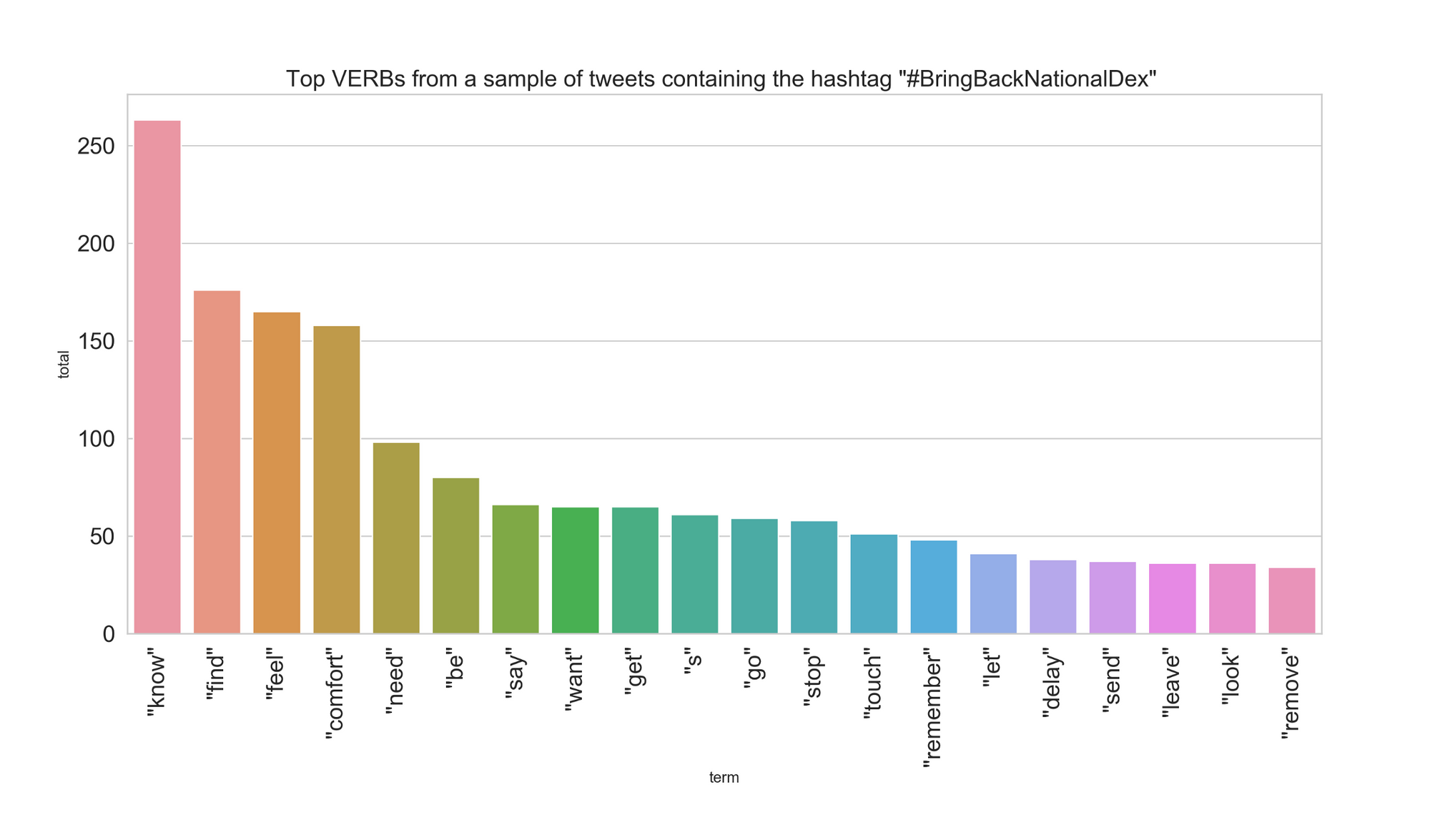

The second POS I want to introduce are the verbs. With the nouns, we learned the main things the users were talking about, and now with the verbs, we’ll discover the actions that complement those nouns. The plot below displays the top 30 verbs.

The first term is a clear example of what the internet wants in these situations: to “know,” to demand information or to ask for explanations. The following term, “finds,” refers to people hoping that their favorite Pokemon find their way into the game. Then we have “feel,” which mostly come from users stating their opinion, “comfort,” which is part of the Wingull tweet mentioned above, and “need,” maybe because for reasons similar to “know.”

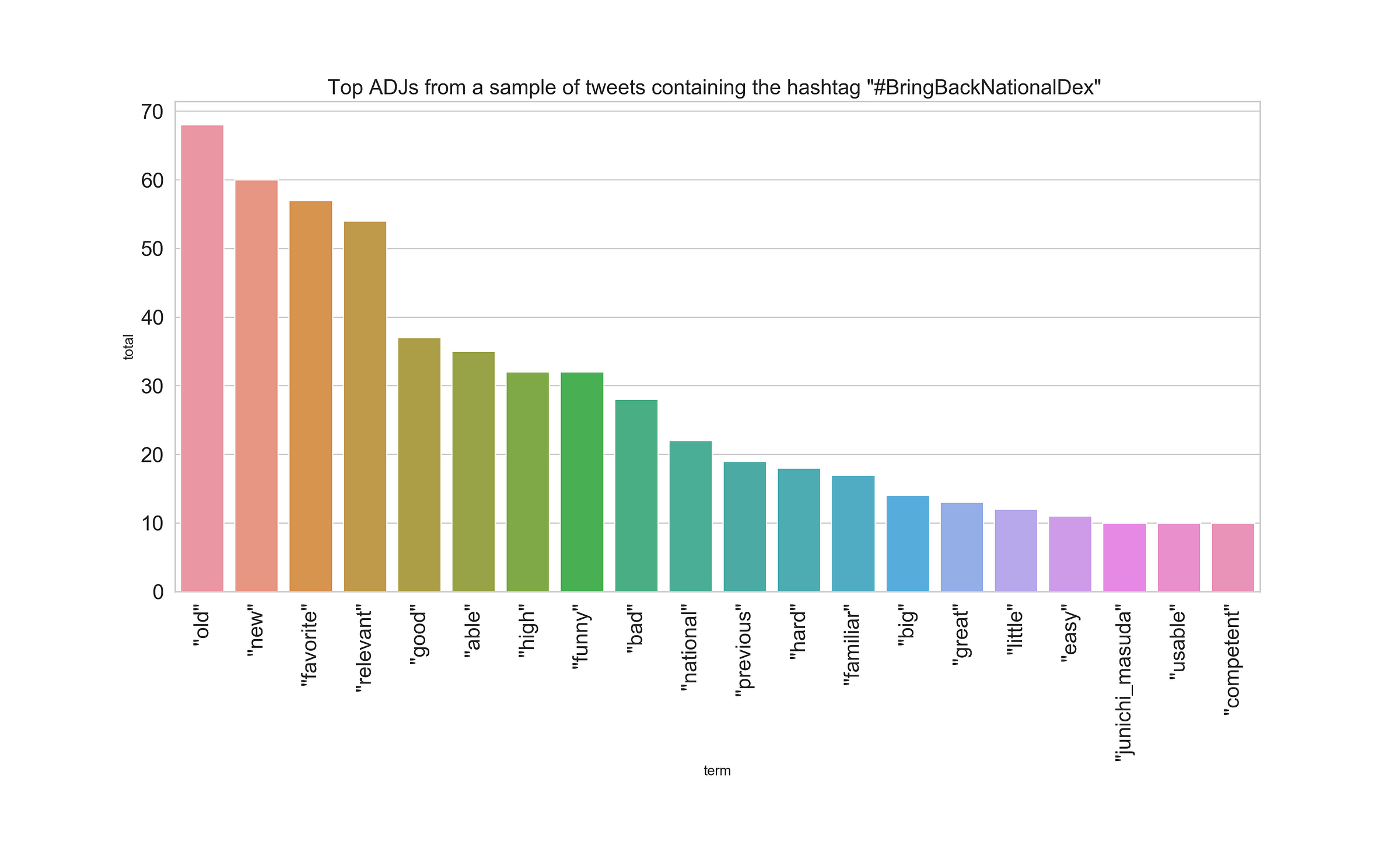

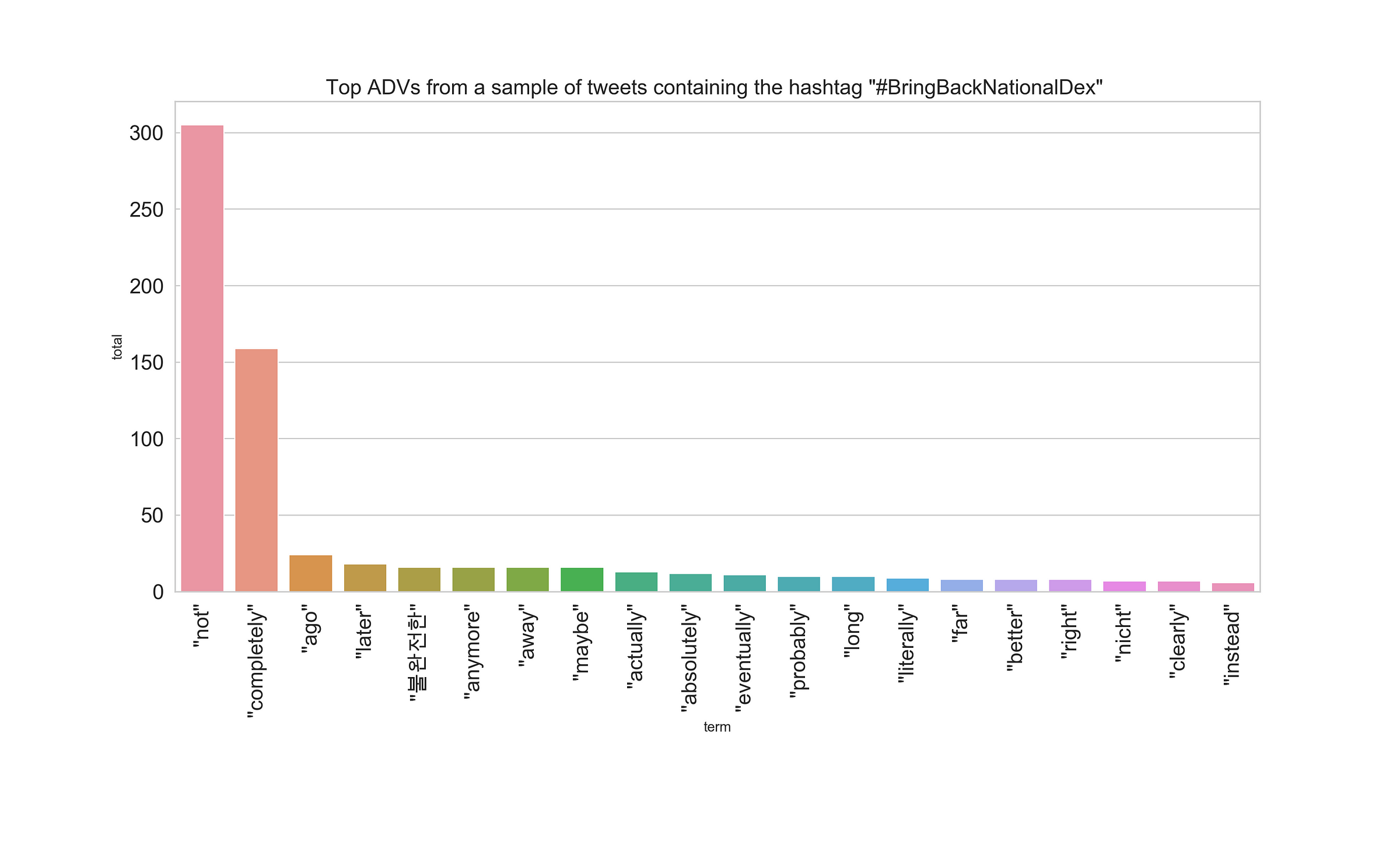

To add further context and refinement to the terms presented, I calculated the adjectives and adverbs; two grammatical concepts that are there to describe and modify nouns and verbs, respectively.

The image above is about the top adjectives. The first term on the graph, “old,” concerns a retweet that said something along the lines of “even if the topic [the Pokedex issue] gets old, I’ll keep talking about it.” Then, in the second position is the word “new,” and in most cases, this adjective appears in tweets that bash some of the new features of the game, or in another retweeted tweet about some new video that talks about the controversy. The third adjective from the list is “favorite,” and it appears in tweets in which users are talking about their favorite Pokemon and the possible omission of them. Other terms that caught my eye were “previous,” “usable,” “competent,” and “junichi_masuda,” who is the director behind the games. However, having this name here labeled under adjective might have been a false positive prediction from spaCy. Now that we know how the nouns modifications, let’s take a look at the adverbs.

The most popular adverb was, “not,” and it emerged in tweets that hint a negative feeling (we’ll see more of this soon) or a sense of disagreement. Some examples are “…do not trust Game Freak”, “I’ll not buy the game,” or “the game will not have the National Pokedex.” Then, we have “completely,” which comes from the Wingull tweet, and after it, the adverb “ago,” mostly used in tweets in that compare the upcoming game with the ones released years ago. Other interesting adverbs are: “later,” “불완전한” (“incompletely” in Korean), and, “eventually.”

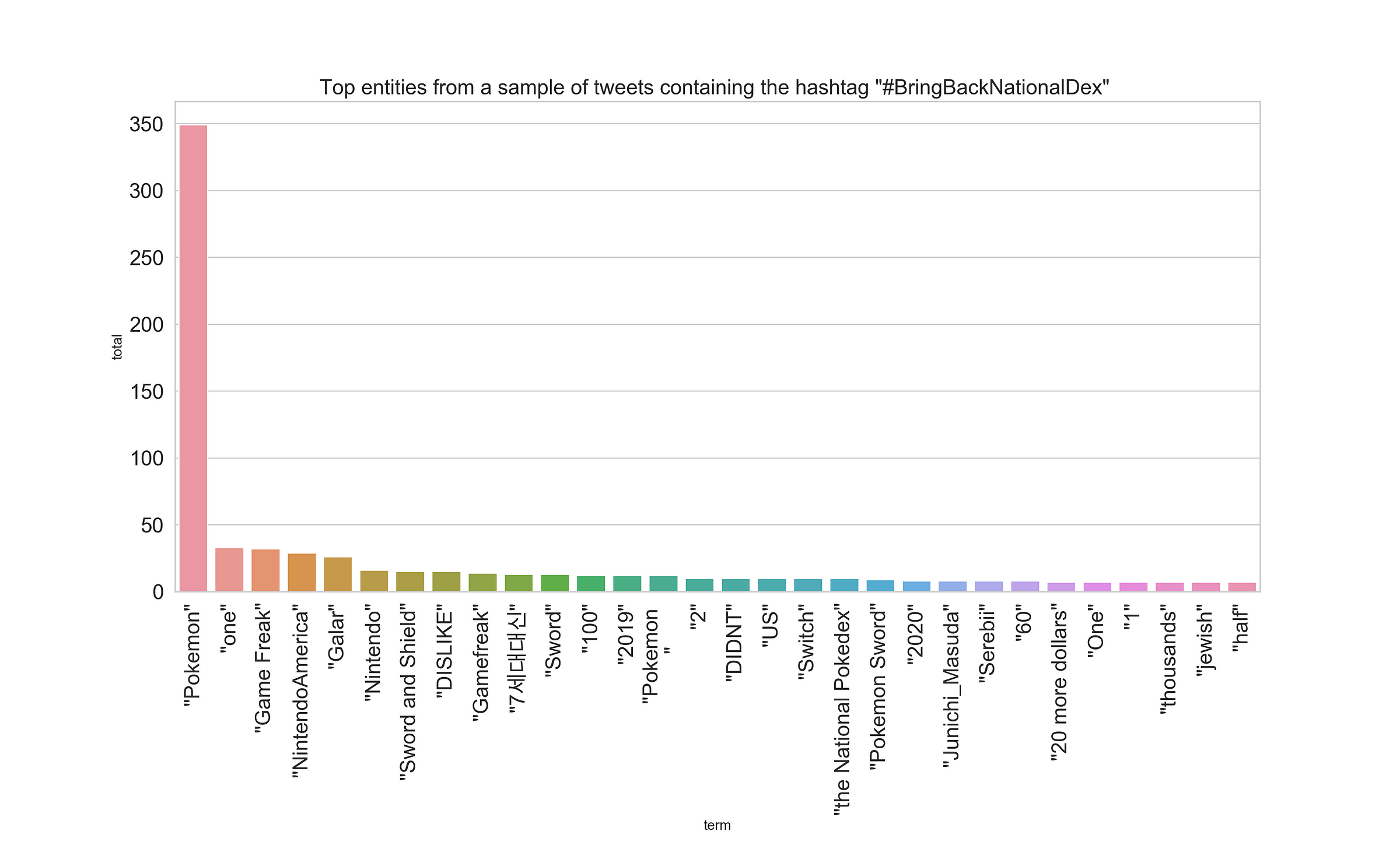

Now, let’s shift our attention from grammar and part of sentences to the entities of the corpus, that’s it, the particular and existing things people discussed in the tweets.

The leading entity is “Pokemon”. Then, we have “one,” used to refer to “this one game,” or, “this one [Pokemon] generation”, and “Game Freak,” the developers at the center of the controversy. Moreover, other recurrent entities are Nintendo of America’s Twitter account, “NintendoAmerica,” and names such as “Sword and Shield,” and “Junichi Masuda.”

Sentiment analysis

Usually, in such controversial events in which the internet become a bit angry and tense, things tend to get a bit out of hand. Sadly, when this happens, people choose to react and comment in negative and even hateful ways. To test this hypothesis, I ran the tweets through a sentiment analysis engine to quantify the “positiveness” or “negativity” of its content. The sentiment model I used is the one provided by Google Cloud’s Natural Language API, mostly because I like how it splits the corpus into sentences to calculate the sentiment of each, and since it is an API, it means that you don’t have to install, train, or download a model.

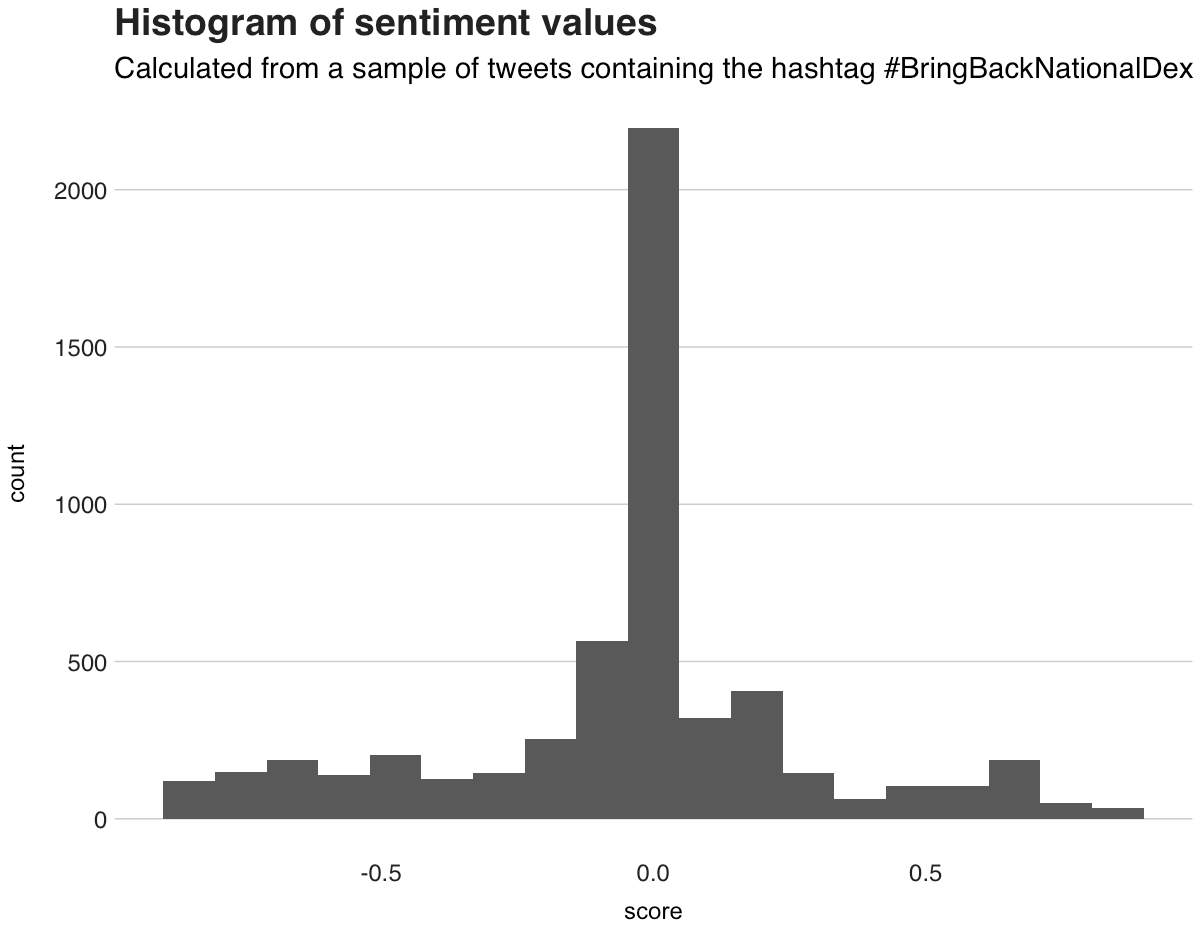

In total, Google delivered the sentiment of 5501 sentences it detected. Each of the sentiment output consists of two values: the “score” and the “magnitude.” The former is a value between -1 and 1, where -1 indicates a negative emotion, and 1 means a positive feeling, while magnitude, which I won’t use here, specify “how much emotional content is present within the document.” The histogram below shows the distribution of the sentiment values.

Surprisingly enough, the sentiments are almost perfectly balanced; the mean value is -0.045, with a standard deviation of 0.27. The peak in the center of the histogram indicates that most of the tweets had no emotion at all, and upon manually inspecting the tweets and the values, I found out that these zero-valued tweets are those made of only hashtags, so no emotions at all. Regarding the ends of the distribution, we can see that there are more highly negative tweets, than highly positive. Some examples are: “THEY RUINED THE SAGA!”, “Pokemon fans: BOYCOTT NINTENDO AND GAME FREAK,” and “THAT GAME IS SO BRITISH THEY ARENT EVEN LETTING POKEMON FROM OTHER REGIONS IN.” On a more positive note, we have hopeful comments such as: “[sic] Im still gonna get it, but [sic] i have great fears my team wont be in the game and [sic] i really [sic] dont like that #BringBackNationalDex,” “It’s amazing to see how passionate the pokemon community is about the games, #BringBackNationalDex is a true example,” and “We follow your game [sic] atleas 10++ years, [sic] pleased don’t betray us, I buy switch just only for.”

Mentioned Pokemon

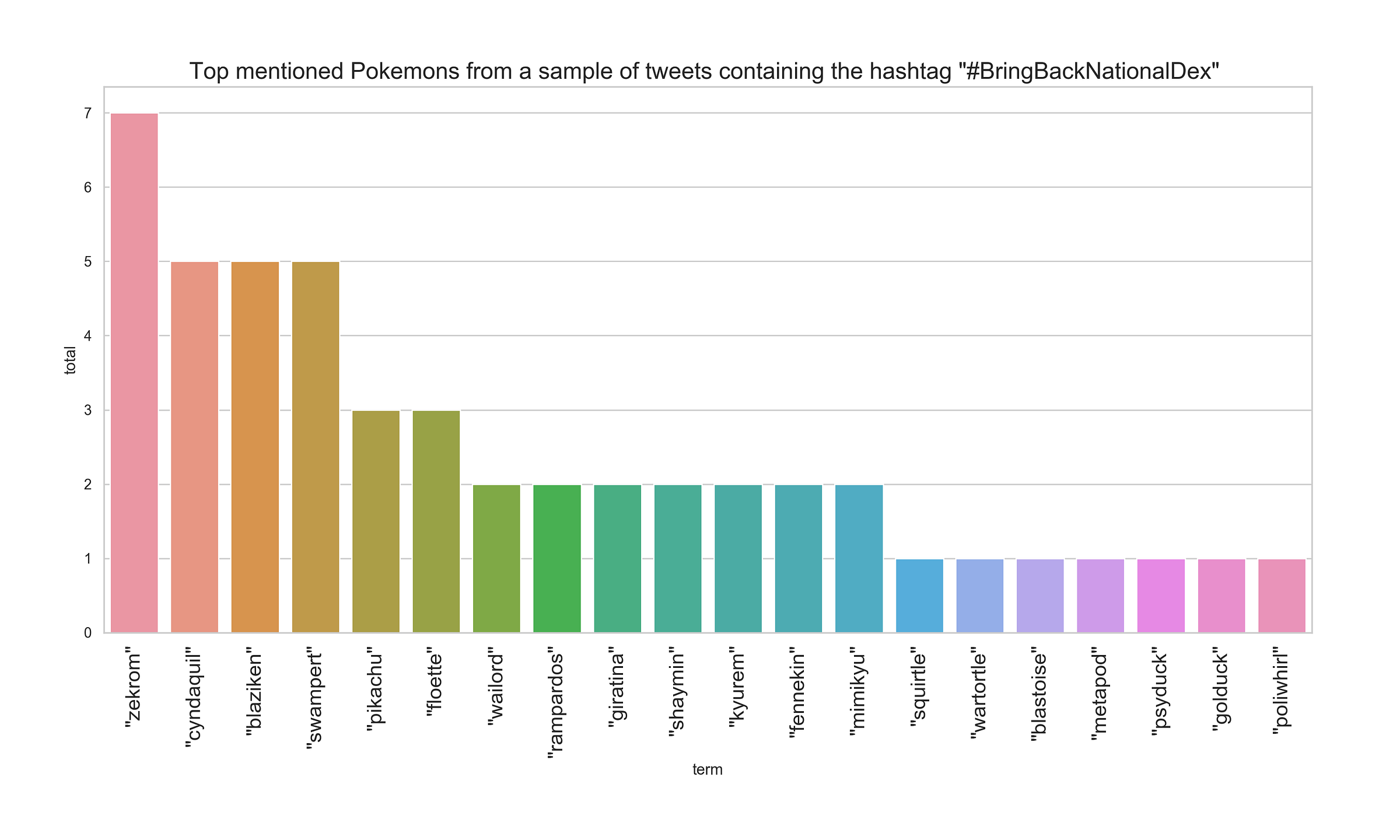

Before I finish this, I want to show the Pokemon that appeared the most within the tweets. Except for Wingull, which appears 160 times in the tweets corpus thanks to many retweets, I found it curious that there are not many mentions to Pokemon. Also, as you’ll see, Pikachu is not the top.

Zekrom, a legendary Pokemon from the fifth generation, is at the top of the list. Following it, there are starter Pokemon — Cyndaquil, Blaziken and Swampert–, and then on the fifth position we have Pikachu.

Conclusion and recap

Twitter doesn’t waste any time. In times when the community decides to be against or in favor of something, they’ll rally together under one hashtag to make themselves heard. In this article, I shared the findings I discovered after investigating a sample of tweets that contained the hashtag #BringBackNationalDex, created in the wake of the announcement that the upcoming Pokemon games won’t feature the complete roster of creatures.

In the first part of my investigation, I used the NLP library spaCy, to discover the top nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs used with the tweets. Here, I found out that the overall meaning behind the tweets was a demand for answers, a sense of disappointment, and even sadness upon the news that their favorite Pokemon might won’t be able to cross the border to Galar. Moreover, to understand the overall feeling of the tweets, I calculated their sentiments using Google Cloud’s Natural Language API and conclude that while some people were angry, others were full of hope. Lastly, Zekrom, not Pikachu, was the most mentioned Pokemon from the corpus.

Thanks for reading :)

The code and dataset used for this project are available at: https://github.com/juandes/bring-back-pokedex-nlp